This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Pair Programming AI Agent

Table of Links

1.3 Other Gender Identities and 1.4 Structure of the Paper

3 Original Study (Seville Dec, 2021) and 3.1 Participants

3.3 Factors (Independent Variables)

3.4 Response Variables (Dependent Variables)

4 First Replication (Berkeley May, 2022)

5 Discussion and Threats to Validity and 5.1 Operationalization of the Cause Construct — Treatment

5.2 Operationalization of the Effect Construct — Metrics

5.3 Sampling the Population — Participants

6.1 Replication in Different Cultural Background

6.2 Using Chatbots as Partners and AI-based Utterance Coding

Datasets, Compliance with Ethical Standards, Acknowledgements, and References

A. Questionnaire #1 and #2 response items

B. Evolution of the twincode User Interface

C. User Interface of tag-a-chat

4.2 Experiment Execution

The experiment execution at the University of California, Berkeley followed the same process than that performed at the Universidad de Sevilla with some changes, which are described in the following sections.

\ 4.2.1 Bonus for participating in the study

\ As commented in Section 3.2, in the original experiment the participation in the study counted for a 5% bonus on students’ grades in the Requirements Engineering course they were enrolled in to prevent dropout. In the replication, considering that the students were enrolled in two different courses with different professors, they were offered a $15 Amazon gift card for participating actively in the study instead of a grade bonus which would have been difficult to manage. In our opinion, this change did not affect any type of experimental validity.

\ 4.2.2 Location of students and number of sessions

\ In the original experiment, the experimental execution took place during one of the laboratory sessions of the Requirements Engineering course, as shown in Figure 4. The three groups of the course had the laboratory sessions the same day at different hours, with 30 students per session on average. In the replication, the students performed the experimental tasks remotely, coordinated by one of the experimenters using Zoom. There were four sessions that took place during a week with 10 students per session on average.

\ We think that this change increased construct validity with respect to the original study, since the setting was strictly remote rather than being co-located in a laboratory room, but it also decreased internal validity because of the lack of control of the subject’s environment, in which interactions with a third person, interruptions, or distraction could occur. On the other hand, having multiple sessions over a week rather than having three consecutive sessions on the same day also decreased internal validity due to the possibility of some students disclosing the purpose of the study to their peers despite being instructed not to do so.

\ 4.2.3 Timing of the tasks

\ In the original experiment, the students were given 20 minutes for the pair programming tasks, 10 minutes for the solo task, 10 minutes for the first questionnaire, and 15 minutes for the second and third questionnaires. In the replication, the students were given 15 minutes for the in-pair tasks, 10 minutes for the solo task, 10 minutes for the first questionnaire, and 10 minutes for the second and third questionnaires, due to the constraints imposed by their busy schedule.

\ We think that the shortened duration of the in-pair tasks and the second and third questionnaires may have compromised construct validity by reducing the time

\

\ span for measuring the response variables, the interaction time for assessing the partners’ skills, and the reflection time before answering each response item. Moreover, it may have weakened the effect of the treatment over confounding variables, thus decreasing also internal validity.

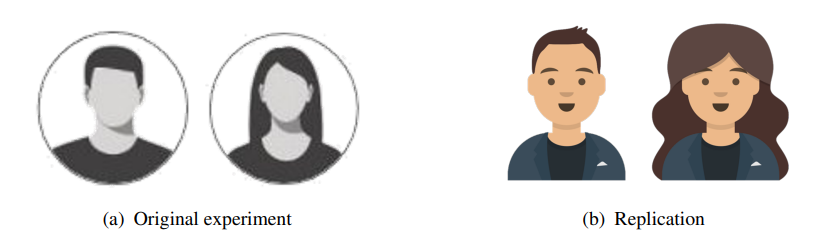

\ 4.2.4 Gendered avatars

\ In the original experiment, the gendered avatars used in the chat windows of the subjects in the experimental group were the silhouettes shown in Figure 9(a), whereas in the replication the avatars were those shown in Figure 9(b), which were generated at https://getavataaars.com/. The subjects in the replication were also shown a gendered message at the top of the chat window indicating that their partner was connected, e.g. “Your partner (she/her) is connected” (see Figure 16(a) and 16(b) in Appendix B).

\ In principle, changing the gendered silhouette avatars by more explicit ones and adding a gendered message in the chat window would have increased construct validity, but the correlation between induced gender and perceived gender in the replication worsened with respect to the original experiment (see Section 4.3.1). As a result, we consider that this change decreased construct validity.

\ 4.2.5 Exercise assignment

\ In the original experiment, the programming exercises, which had to be solved using Javascript as the programming language, were randomly assigned to the subjects from a pool of exercises of similar complexity. In the replication, the programming exercises, which had to be solved in Python due to the background of the participants, were organized into two blocks (A and B) that were randomly assigned to the subjects during the experiment.

\ In our opinion, adapting the programming language to the background of the participants should not have any impact on experimental validity, but using two blocks of exercises instead of a pool of exercises definitely improves the blocking of the related confounding variable (see Section 3.5.2), thus increasing internal validity.

\

:::info Authors:

(1) Amador Duran, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain (amador@us.es);

(2) Pablo Fernandez, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain (pablofm@us.es);

(3) Beatriz Bernardez, I3US Institute, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain and SCORE Lab, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain (beat@us.es);

(4) Nathaniel Weinman, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA (nweinman@berkeley.edu);

(5) Aslıhan Akalın, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA (asliakalin@berkeley.edu);

(6) Armando Fox, Computer Science Division, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, USA (fox@berkeley.edu).

:::

:::info This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.

:::

\

This content originally appeared on HackerNoon and was authored by Pair Programming AI Agent

Pair Programming AI Agent | Sciencx (2025-06-24T16:30:04+00:00) What Happens When You Change the Rules of a Controlled Experiment?. Retrieved from https://www.scien.cx/2025/06/24/what-happens-when-you-change-the-rules-of-a-controlled-experiment/

Please log in to upload a file.

There are no updates yet.

Click the Upload button above to add an update.